SHUFFLING MY CARDS

Life in Australia is hard and ruthless. No matter how rich people are, most live on the edge of their financial capabilities. Here, you always pay too much. Everything is too expensive. Everyone has to make maximum profits to survive. You never pay the actual price, and the profit margin is three to four times higher than in Europe. Even poor quality gets sold for horrendous amounts. In addition to products, every experience gets treated just the same. In the end, even with personal contacts, often only one thing counts the money. To get paid, it is morally justifiable to do anything you can. I'm thrown into situations that leave me speechless.

TUKETI-TUKETI

After ten days in the pearl of Southeast Asia, I finally move on. This time with a slow boat to the Thai border. At short notice, I decided against exploring Laos. The north is green and beautiful. However, I have already seen jungles in Nepal (three and a half months), southern China and now also Laos. I'm not interested. So I continue.

IN THE OVEN: LUANG PRABANG

As soon as I wake up, I pack my things and go to my reserved hostel in the centre of the city. In Luang Prabang, the centre consists of a hill with a temple and the main road lined with stone houses left by the French colonial rulers. An ensemble, which in its entirety is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

SLIDING INTO LAOS

As soon as I am at the border checkpoint, I get back on my bus and leave the golden building behind me. To the right and left of the road, a hilly landscape spreads, densely overgrown in a thousand different shades of green. It reminds me a lot of Nepal. There's just one difference (besides all the obvious ones). Currently, there are no dusty mountain slopes and the like. Long live the rainy season.

HISTORIC REMAINS

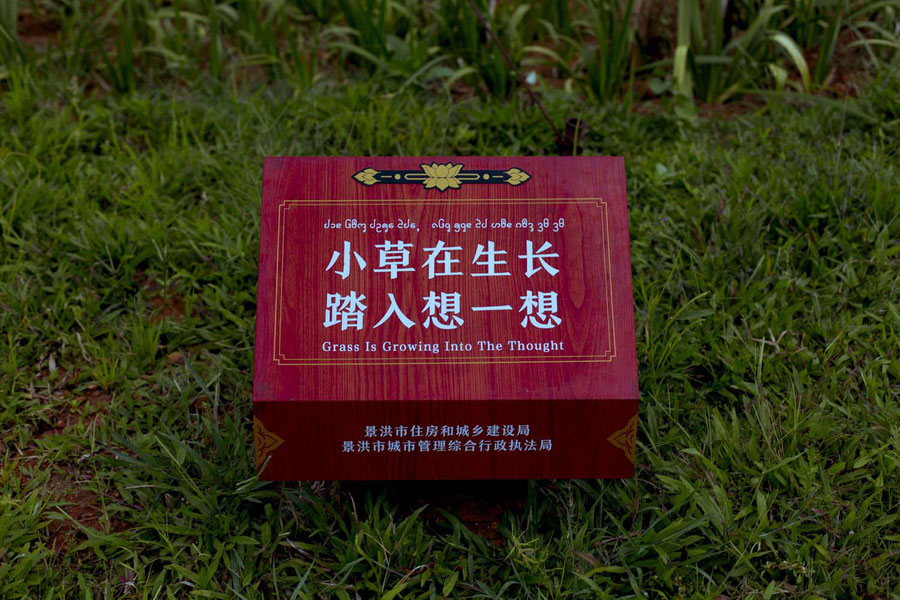

Jinghong is a young city. If you want to know something historical about this area, you have to follow the minorities. The most prominent here are the Dai. One morning C. and D. take me to the mountain, at the foot of the river Lancang and a nameless sidearm, to show me the oldest part of this city.

CHINESE TEA

One of the biggest gifts that C. and D. give me is the introduction to Chinese tea. I spend some time looking at the world map in the common room while C. prepares it.

VISITING THE ZERO FACTORY HOSTEL

I follow C. through the hot streets of Jinghong, smiling. We got out of bed early today, to experience the market in full swing. Although it's just 7 o'clock, the sweat is dripping from my forehead and my spine. My cotton clothes are too heavy and too thick. It's unthinkable to wear jeans. The silk clothes from home that have been with me these two years have become threadbare. All that's left is a skirt and a fluttering yellow dress. My wardrobe just isn't up to snuff anymore. It's ideal for a day watching Netflix, but a bit flashy for a market day on which I'm supposed to photograph the "locals" in their element. A task I'm reluctant to do anyway, but since I will not use the pictures myself, I agree. I haven't fully understood what my hosts are hoping for from my work, but since they cannot explain it to me, I assume they don't know it themselves. So, I do what makes sense to me and hope that they can use it. I feel like that's all I can do.

STONE FOREST

The Stone Forest tears a big hole in my budget. First, I decide not to visit it at all. But meeting N. makes a trip out of the city seem possible. I decide against my initial gut feeling and am ultimately convinced by the beautiful photos. It's one of the excursions that I bitterly regret. China is a stronghold of controlled tourism. Everything is organised, everywhere you have to pay unwanted fees, buy the ticket in places that are miles away and in the end you get a Disneyland experience.

THE LONGEST TRAIN JOURNEY SO FAR

From the centre of Lhasa, I fight my way to the station. Because of miscommunication between the receptionist and I, the taxi driver demands me to pay 50 yuan for a 15 yuan journey. I stay in the back seat for a whopping 20 minutes. Finally, I give him the 30 yuan that stand on his meter. He is offended and I am annoyed. Because of my little standoff, I have thirty minutes left to catch my train. The train station square is vast. To get to the entrance I have to walk in serpentine lines across the square, through two security checkpoints and into a separate building to get my ticket. I stand in line for 20 minutes. When it's finally my turn, my phone does not load the file on my ticket number, because it was sent to save space in the cloud, so that only a pixelated black and white image can be seen. I break a sweat, I act innocent and present my ID. Fortunately that's enough. She gives me two tickets and I drag myself out to walk to the main building, where I suspect the train station. Bingo. I find train station boards and uniformed officials, who now control my passport for the fourth time and now also my tickets. Since I can not decipher the Chinese characters, I follow the crowd. Although the train station in Lhasa is a vast facility, only one train leaves.

THREE DAYS ON THE ROOF OF THE WORLD

The roof of the world is very different from what I imagined. The mountains in Tibet look like the perfect backdrop to car adverts. Like the Swiss Alps minus the Christmas trees and alpine huts. The streets are new and nestle into the mountains like snakes. It's fantastically beautiful. Quickly enough, we leave the views into valleys behind us and climb onto the plain on which no trees grow and the only green springs from a touch of moss or turquoise lakes. They reflect the endless expanse of the sky. The landscape up here is unique. If pressured I'd compare it to Armenia or South Iran. However, Armenia and southern Iran are mostly yellow. Tibet is brown. It's a rocky desert where no tree or bush protects the people from the glaring sun.

THE GATE TO CHINA

A simple black gate on the Nepalese side transforms into a concrete castle on the Chinese side. A little shy, I walk past the guards in the hope that they will ignore me. And they do. The concrete building has two wings. On one ARRIVAL is written, on the other DEPARTURE. I go to the ARRIVAL terminal and am promptly called back by the Chinese Officers from within the building. “Not a step further, young lady!” I am put on a green plastic bench, and I wait. I write an e-mail to the travel company because my Nepalese sim is still working. They were supposed to pick me up from the border in the morning. Since Tibet is two hours ahead of Nepal, I left early. In the end, I arrive at the border around 9 o'clock (what I believe to be late), and still, nobody is there. I'm waiting for a total of five more hours because of a spelling error in my paperwork. The Chinese accept only perfect papers. My travel company seems to have its hands full as they forget me for four more hours. Everyone is friendly. It sometimes seems, exclusively to me (to the other travellers and the Tibetan guides, the officers are rude at best). I got my privilege back. It can have advantages to be a woman.

GOODBYE NAGARKOT, GOODBYE NEPAL!

Eventually, I hitch a ride to Bakthapur with a Nepalese couple and share a taxi for the last section to the capital with an older lady who has now emigrated to America. Such small encounters give me a lot of joy, but I forget them almost as soon as they happen because they add up and then merge into one in my memory.

HOLI

Barely dismissed from the convent and it's Holi. Holi is known as the Indian Color festival around the world, but it's much more than just a celebration of the powder that people throw in the air that day. Spring is welcomed and every color brings a blessing. Here it's the first hot day. We only experience what is happening on the streets: a colourful powder and water battle. It's one of the oldest Hindu holidays and not unlike our carnival in some aspects. For the first time, we experience the Nepalese without the social restrictions of the caste system and full of exuberance, with a healthy dose of alcohol in their blood. The locals, who usually appear to be so peaceful, now show their playful and mischievous nature and chase us through the streets. Small children throw water bombs from the safety of the balconies and test the limits of the adults. It's no wonder that this feast is popular around the world. Only from women, I hear contrary opinions. Women of my age mostly don't participate. Younger girls crave the taste of freedom that this festival offers them. The result is drunkenness, but the girls always remain in groups. I feel very uncomfortable in the crowd, the stress and the feeling of being hunted don't leave me. I realise, once again, that I don't tolerate wanton men. Here too, the playful atmosphere is used to feel up asses and breasts and to rob unwanted kisses. It's the same everywhere. Once again it's shitty to be white and overly visible.

TIBETAN NEW YEAR: LOSAR

Over the walls and the floor, I feel the vibration of the gong more than I hear the sound. Together with bells, traditional oboes and the never-ending Tibetan laryngeal song, that echoes over the speakers like a rattling chainsaw, it provides a beautiful yet profoundly foreign soundscape. I'm in the back of the stupa, in the hierarchy behind the Lamas, the nuns and monks. They are between five and a hundred years old, sit in rows, separated by gender, not strictly, but sorted by age. At the rear end, near me, the youngest nuns sit in groups, separated by older sisters, who regularly call them to order, give them sweets or arrange their clothes. The young monks and nuns often come to the monastery school very early in their lives. They seem terribly young and fragile to me. I can hardly imagine how cruel it must have been to leave one's own family so early, yet they all look happy as they sit there in line with their older sisters and brothers.

SPIRITUAL DETOURS

Back in Pokhara, I'm in the shower for the first time in five days. I let the water fall over my shoulders, enjoy the warmth that brings my muscles long-awaited relief and the smell of shampoo. My legs hurt after the day's march downhill. Each step is a reminder of what I've just accomplished. After showering, I stretch out on my bed and promptly fall asleep. Eventually, S. wakes me up. While I did the Mardi Himal Trek, she did the Poonhill Trek and together we are planning to travel to Kathmandu. She is on a spiritual journey, was in an Ashram in India and wants to go to a Buddhist monastery here in Nepal. I am curious and join her.

AT 4.500 METERS

When I leave my dorm at 4:30 am I don't hear a sound. I get dressed, get ready and step out of the hut. The starry sky is clear, the moon shines bright, but I'm the only one out. The others are probably still sleeping. I'm a little scared that if I lie down again, I will not go up the last bit of the trail. After all, I know now that it gets damn exhausting and I don't feel so fit. My headache has come back, but I don't think about it. This time I leave without luggage. Without breakfast and with a bottle of water in my backpack, I find my way with my headlamp. It's difficult to see the beginning because the path is marked only when it is steep. Down here in the meadows there are just a few well-trodden paths that either lead to the trail or into nothingness. Soon, however, I am standing in front of the first marker and keep pushing ahead.

ONE FOOT IN FRONT OF THE OTHER

I have read so many old texts and stories, but I only understood how it feels to be thrown around a carriage for twenty kilometres, since I drove from Pokhara to Phedi, unbelted and in the back seat, with an annoyed taxi driver. Memorable. When I get out, it takes me longer than usual to understand where I am in relation to my map. He had dropped me off on a new path not yet on my map. Since it's parallel to the older earthquake-damaged road, it doesn't matter. I allow two local ladies to guide me over the water and the hill, and find myself on the bottom of the stairs that will bring me to the desired village. A few small stalls are selling water and chips along this busy part of the street. Since I am well prepared, I refuse the offers and put my foot on the first step. With me, a group with twenty people arrived with a guide and several porters. Since, surely, they will go the same way, it's my firm desire to be well ahead of them. I throw myself into the inevitable without hesitating.

THE LONG WAY TO NAGARKOT

Every now and then something grabs my attention. I have a random idea, and nothing will make me change my mind. That's how it has to be done. It happened in Poland, Georgia and now here in Nepal. I want to trek from Bakthapur to Nagarkot. It should be about 15 kilometres. That's possible, I decide. I shoulder my backpack and take my first step. I walk out of the city, into an industrial area and then up the rural mountain. I didn't think of the mountains. Not really. They go uphill, of course! Consequently, I have to take a break every ten yards. Upward, a normal pace is impossible to maintain. I have scheduled four hours for this trek, which, of course, isn't enough. I get invited by friendly Nepali ladies to a deep-fried bakery for a break and then I slowly progress up the hill, accompanied by two young girls. We quietly pass the stupa. My uphill battle doesn't stop. I don't see anyone else walking this route. The locals seem surprised to see a tourist on their street. My head is red as a strawberry, I puff like a locomotive, and the water runs down my back in streams. I am a sight for the gods. But that's the beauty of trekking, I tell myself. All vanities fade. I'm in the here and now, busy putting one foot in front of the other.

THE JUNGLE OF CHITWAN

We walk to the river, where a small group of people is waiting for us. The narrow boats, carved from ancient logs, lie in the shallow stream of water and proudly point into the white fog. The river seems wide. We don't see the other shore, and all sounds are muffled. In a group of five tourists and four tour guides, we settle into the boat and sit down carefully. One by one, so that no one falls into the crocodile populated water. For half an hour we stay in the boat with our legs pulled to our chins. The humidity creeps into our clothes, and the cold settles into our bones. My joints start to hurt. The trees on the shore and the turquoise water, both almost covered by fog, are our constant companions. Our guides show us the species of birds they know. They are all new to me. We're lucky and see a little crocodile sleeping on the shore. His body is half in the water, and thin grass camouflages the rest. If it gets hungry, it will be easy for it to catch a bird.

NEPAL, I'M COMING!

On the other side of the border, houses are tightly nestled together. Although the road is worse on the Nepali side, people are calmer. Nobody speaks to me. When I ask for information, they give me a direct and uncomplicated answer. I go to immigration, get my monthly visa and pay my fee in Indian rupees. Many reports have prepared me for possible corruption and yet I don't encounter any. When I buy a bus ticket, I pay less than they say on the internet. My salesman takes me right up to it, politely explains where I should get off, checks several times if I don't want to have breakfast and makes sure my backpack is safely in the back. I watch him suspiciously at all times. I can't believe that they aren't trying to scam me. Nothing happens. I am no longer in India. The people are different, definitely friendlier.

MOVING ON

Blue-eyed and unaware of anything, I make my way to the bus station in the darkness. I had to poke my rickshaw driver vigorously in the back to make him drive in the right direction. When I arrive, I am so happy to be in the right place and to have found the correct bus station, that, at first, the narrow seats and the missing headrests don't worry me. I'm one of the first to get on the bus, but soon it gets jam-packed. When asked if a young man can sit next to me, I stubbornly refuse. It's too tight. I don't know what he will think when my hips are drilling into his. So, a young woman has to change her place. She seems reluctant to be removed from her father's side, but I'm okay with that. I cannot face an eight-hour drive if I have to worry about the man sitting pressed against me. In this situation, I realise how much I have changed. I am glad and a little bit proud to have stood my ground.

OF BEAUTIFUL MEN AND EXPLODING CARS

Bollywood. As I watch a homeless man being robbed on the street in Jaipur, I stare at two glass panes simultaneously. The television, in which a Bollywood film is playing is reflected in the polished window of the hang out space, behind which the harsh reality takes place. I experience this contrast as tremendous. Never before has it become more apparent to me how reality and fiction relate to each other. As I share my observation with my American acquaintance sitting next to me, she coolly responds that it's the same with Hollywood. Since I have not yet been in America, have no concept of reality there, and everything I know about the country comes from history books and the moving picture, this analogy surprises me. After all, Bollywood is so obviously unrealistic. Hollywood, on the other hand, at least tries to maintain a certain amount of reality, (I thought.)

HEADING TO THE GOLF

I returned from Tehran without having achieved anything. Once in Isfahan, we boarded a minibus in the darkness that would take us to the south of the country. When the roof was loaded, the backpacks tied and all men were on board, we closed the curtains, turned up the music, and the party began. One by one the others got up from their seats and danced in the narrow hallway while the bus roared through the night. Only with difficulty (and a bit of rudeness), I managed to avoid the dance requests. Dancing in Iran is unpleasant. Once again, I am in a situation I would love to run away from, fast. But here there was just one way out. I closed my eyes and pulled myself back into my head. There it was peaceful, far away from bad jokes and overbearing personalities. I had lost my tolerance and the ever-present desire to openly welcome cultural encounters. Something in me had died during the past weeks, and I couldn't connect to my innate curiosity for strangers and other cultures anymore.

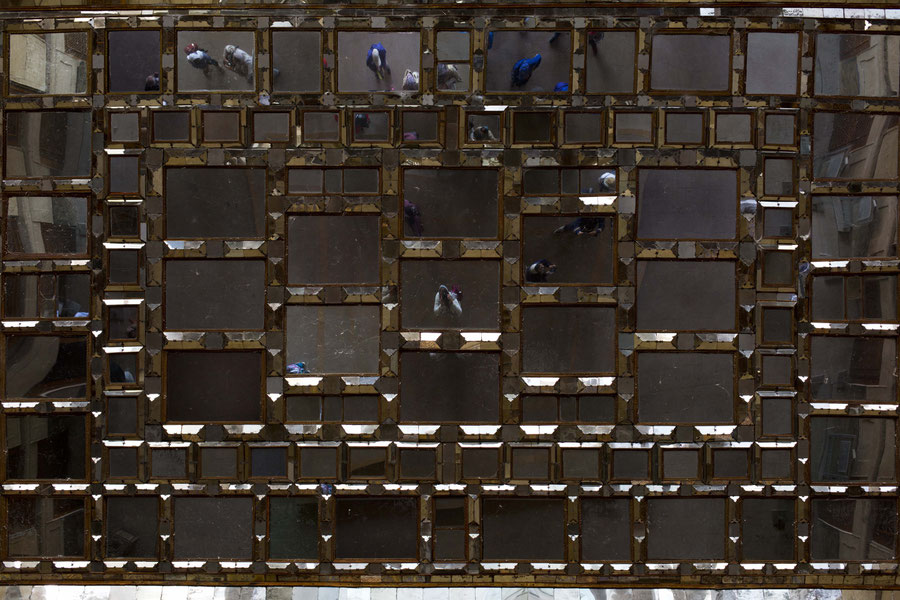

ISFAHAN or M&M

Isfahan is rightly one of the principal attractions of Iran and a vital part of my experience, not because of the magnificent palaces, the beautiful fire temple or the prominent mosques, but because I got to know M. & M. They offered me room and shelter in exchange for English language training. They were different from the other Iranians I had met so far. They were living full lives and tried to live according to the rules of their country. They were not overly religious, but they were believers, still.

DESERT DREAMS

Never before have I seen something as beautiful as the Maranjab desert. I'm a desert virgin. My reaction is typical for a European desert virgin: my mouth catches flies.

LET'S GO TO IRAN

The bus ride to Iran is an adventure. R. (from Alaverdi), who happens to be in Yerevan on my last day, drinks coffee with me and puts me on the crowded bus. I'm sitting in the back, with a pack of men. The women are all in the front rows. Here, I get a taste of what awaits me in Iran. Fortunately, I have a single seat that is separated from the gang of young men travelling in the back of the bus.

A NEW BEGINNING

Georgia. The Caucasus begins here from one second to the next. At the place where my Russian taxi driver drops me off, the valley is broad, and the mountains look like adolescent boys. The border crossing to Georgia is one kilometre south in the notch of a mighty canyon. The three thousand meter high peaks rise in self-confidence on all sides and command awe. Instead of the military, the border is guarded by a monastery. There, I take my first break and congratulate myself on crossing the border. I have started to celebrate the small stages because sometimes the stretch in my head is so much wider than the kilometres, I physically travelled.

ICE, ICE, BABY!

The slow awakening of nature fascinates me. I've never experienced spring like this. For three, maybe even four weeks, it didn't freeze during the day. There is still snow in the ditches and along the Volga beaches. There, the sand is visible now, and the last bits of thick ice linger on shore. On some afternoons I can imagine how beautiful summer will be. The ice pieces are still large in some parts of the beach. They are too heavy for the water to move them. The small waves of the river, not yet open for ships, splash softly against the ice and create little cavelike cliffs. They form a surprisingly solid ice roof that reaches out daringly over the river.

DANGEROUS RUSSIA

Originally, I wanted to write about pancakes. But when I walked across the street this morning, I changed my mind.

BENEATH THE SNOWCOVER

People say there are only two seasons here in Samara: the summer and the winter. Spring and autumn are short, almost unnoticeable. Of course, this is only true if you think that winter lasts as long as snow is falling and summer as long as it doesn't rain. Of course in actuality, you can feel, see and smell both spring and autumn (I presume).

THE VOLGA

... is really wide in Samara. I first encounter her covered under a thick layer of ice. Crossing her is easy, and kind of the next best thing. So that's what we do. It takes an hour and a half before we arrive on the island, which lies before the second much narrower half of the stream. The road is patrolled daily and thus deemed secure. Although the snow is pressed where we walk, we sink up to our ankles. Only Ева (Jewa), the family dog, doesn't have any problems. She rolls around in the snow and tries to push her nose under the white blanket. The grey sky, the tiny snowflakes and cold wind don't put her off. The rest of the family has already pulled hats, gloves and scarves over the areas of skin exposed to the harsh winds. As we usually do what we set out to do, we walk silently to the island on the other side of the river. There, I see this year's first spotted woodpecker clunking away on the trunk of a birch. Here too, the spring stretches out its feelers defying the thick snow cover. The island is a paradise for hunters and ice-fishers, who we pass in considerable numbers. All are in camouflage clothes, equipped with army green backpacks, frequently pulling ice drills on stretches behind them. As we already observed the marshland and its inhabitants on the island, we decide to go back home and enjoy a hot cuppa instead of walking another hour or two to reach the other side. The way back would be long enough as it was.

MOSCOW

In Moscow, J picks me up at the train station. I'm glad to see his familiar face and enjoy not having to understand anything, just follow along and find most things without looking. I will stay in the capital for only two nights, so we put my luggage away and plunge into the town. I didn't make a city map for Moscow. It's huge, and I know only selectively what it is that I've seen. Most of the things around the Red Square, millions of lights, hundreds of fur coats, (more than five but less than ten) metro stations, beautiful people, supermarkets, statues, churches, parks, shopping streets. At night my legs burn, are thicker than ever, and my knee-caps won't stop hurting.

THE BOTANICAL GARDEN

Saint Petersburg is gorgeous. It's a place where you should spend more than two days. I didn't have the time because I was expected in Samara. Also, I was kind of nervous and had no patience to stand in front of art. So, I decided to ditch the Hermitage (famous art museum) and look at the Botanical Garden instead. It seemed more intriguing to me than European art. I've always been a KINO (Kunsthistorikerin (art historian) in name only) and studied it because I've been fascinated with unusual places for years. History can be exciting (if the backbone is a good story) or (more often) a bore.

HEAD FIRST

When I got out of the train, it was already dark in Saint Petersburg. The train trip had lasted only three and a half hours, and Russia in the north didn't feel too different from Finland. It was a little colder than Vantaa, but except for the big number of people in uniform, the even larger number of women of all ages wearing fur coats, the Cyrillic letters, and the vast range of expensive to cheap cars, the differences didn't seem to be too shocking. In my head swirled all the warnings of people from Russia who had drawn the picture of a wild and ruthless country. Here, however, I found nothing wild or even reckless (not even the traffic!).

ICE SWIMMING

I have buried the idea of ice swimming in Finland somewhere deep in the back of my mind. In my immediate vicinity, there are no Finns who enjoy this sport. At least that's what I think. On one of my last weekends in this lovely country, R. receives an e-mail asking us if we want to try it. S. (R.s friend) has done it some odd ten years ago, knows where to go and wants to take us along. My heart makes a jump and screams: YES! R. gets soft knees. Wading into water always takes some time for her. Wading into 0,6-degree cold water will almost certainly not resemble her idea of relaxation. Seeing my eagerness, she pushes herself and grabs everything we will need: bathing suits, a large and a small towel for showers and the sauna, crocks, beanies and lemonade. In the car, I feel sick to my stomach. I have claimed that this will be great, but I'm not so sure about it anymore. Am I insane? The Finns are crazy. That is undisputed, but me? Why do I want to do this? Swimming in ice is absurd!

SISU

The father of my host family is a former rally driver. If you think of car racing, get away from Formula 1 and look at what Finland has to offer: rallies. Since I have no clue about cars, races and rallies, check out the following video from the BBC's Top Gear. Let me just add; I have found no evidence that what they say in this show, isn't 100% accurate:

THE CURONIAN SPIT

After four days in Klaipéda, where I had either worried about my wallet or had been desperately running from office to office, I decided to reward myself with a ferry trip. I had read on one of the brochures that there was a dolphinarium somewhere on this island and decided to just go there if all else failed. (I've never been to an establishment like this, and had no idea what to expect.)

KLAIPÉDA

Read part 1, 2 and 3 of this story.

This is part 4/4.

When I got off in Klaipeda, the bright red sun stood in the sky. The clouds captured the pink light dramatically. I felt it was worthy of my state of mind and walked towards my AirBnB. Luckily there were city maps in front of each station and there was the internet in every intercity bus. I knew exactly where I had to go. I couldn't take the city bus because I didn't have the 80 cents for the fair. I was moneyless, hungry and isolated in a strange city. (Sometimes this happens really fast...) From the reviews on AirBnB, I knew that my hostess provided a fruit plate and tea for her guests. I would have something to eat, warmth, a shower, a bed and a contact person. It would be wonderful considering the circumstances.

SOMEWHERE = KAUNAS

Read part 1 and 2 of the story.

This is part 3/4

With my big headphones well hidden under my hoody, I sat on a bench in front of the platform where the bus was to leave for Klaipeda. The bus drivers had brought me to the right place. Only now did I realize the degree of their care, and only slowly did I understand that the time zone had changed. Although on my watch it was only four o'clock in the morning and the bus would leave only at 6:25 am to Klaipeda, I had to wait only 1:30 hours. However "only" was relative, since it was cold and dark figures lurked around here. They were as dark as I was... Just to be safe and to look confident I listened to podcasts. I listened to the latest episodes of Reply All, Sampler, and The Guilty Feminist. They always made me smile. Podcasts were something through which I could create a feeling of home instantly during my trip. It's the home between my ears.

All were muffled into their long, mostly black coats. Only on closer inspection did I realize how stylish some of them were. A traveler put his luggage next to mine and asked me something in Lithuanian. I could only answer him in one-word sentences and sign language. He also wanted to go to Klaipeda, but still had to buy a ticket. He left his luggage with me and went to the ticket office. I did not really know whether he was a terrorist or a normal person. I was so entrenched in the terrorist narrative, that It was constantly in my head. He also had a poorly packed something in his hand. It looked like a drug delivery from a movie as it was wrapped in duct tape and had the size of five and a half beer cans. He always carried it with him. I wondered if the bus lines were a frequently used means of transport for drug smuggling... At the end, he even left this parcel next to me and when he took a pair of glasses out of his pocket, he suddenly looked like an architect with a small model of a house. It was really interesting to see how much of my assessment depended on a man's appearance. Spectacles turned a terrorist into an architect. Just like that. Our confidence in each other grew slowly. Meanwhile, we understood each other without words. In the end, I also went to the ticket office and left my big backpack with him. It had occurred to me, that I might get in trouble with my ticket. Maybe I had to buy a new one? Perhaps I had been cheated by the website and my ticket was worthless? The Eurolines bus drivers could have been just friendly and maybe had pity with me? After all, I didn't know. It was lost in translation. In the ticket office, I noticed that my wallet was no longer in my pocket. Instant panic. I now only had my passport. Driving license, all bank cards and my ID card were gone. My head was racing. WHO? WHAT? WHERE?

It must have fallen out of my pocket, on the bus. I was lucky again and my ticket was valid for this bus. The lady hurried after me, as I had gone out of the ticket box in terror about my discovery. I would not have had the money to buy a new ticket and would have been stranded in Kaunas without the Internet, all alone. In the bus I wrote M an e-mail (the student from the bus from Gdansk to Kaunas), she answered almost immediately. Unfortunately, she was already on another bus to Riga but sent me all the addresses I had to contact to recover the wallet. I was infinitely grateful to have met her and that I had already booked an AirBnB. I knew where to go. I just had to put on foot in front of the other.

(the story continues.)

FROM POLAND TO LITHUANIA.

Read part 1 of the story.

This is part 2 of 4.

I had calculated that if I went to sleep at around 8 pm, I could still get my full 8 hours of sleep. It's better not to be hungry or tired when sitting and waiting "somewhere". I was tired but not hungry and decided that, after sleeping, my situation would be improved. Besides, the sun would rise at six o'clock. Once inside a country, you could get everywhere, especially in daylight. As a result of these thoughts, I was pretty relaxed, or rather tense and relaxed at the same time. A new sensation for me.

The young Latvian asked me where I wanted to go, why I traveled, etc. and we started a very nice conversation. Students are similar wherever they come from. We had an incredibly fast developing rapport, a common basis. We exchanged e-mail addresses (divine intervention!!!), talked about my business cards, which she deemed beautiful (yeah! She studied design), and swapped travel stories. For the first time in my life, I had my business card nearby in just the right moment. M was an experienced coach traveler on her way to Riga and once had a long-distance relationship to a German. She spoke all the languages that I didn't and perfect English. She asked about my route and promised to reach out to her contacts in Estonia to organize a couch in Tallinn. What made me most interested in this possibility, however, were the random connections and networks that open up thereby. Before my inner eye, I saw a network of red lines stretch around the globe. They were all the small connections and acquaintances, who got to know each other and through each other all the possibilities, the stories, the angles and point of views. All the small worlds and communities, which are mostly closed and live side by side on the same planet, and only by random encounters, are interconnected and form the red network, which was now vibrating in my head.

For a few hours, I was completely present, reconciled with the world. My trust in the road was deep and I felt safe and secure. The old ladies, who were sitting in front of me and were about to stretch out over all four seats in their rows, were waking at regular intervals to go to the loo. They smelled like the older women in Germany, but their supply baskets were at least twice as big. I was looking forward to the extensive breakfast when I arrived "somewhere" and drank some sips from my bottle. To my astonishment, the bus driver distributed 0.5 litre water bottles to everyone, so that my supply was topped up and I stayed hydrated in the morning. It was the little things on this trip that made me happy.

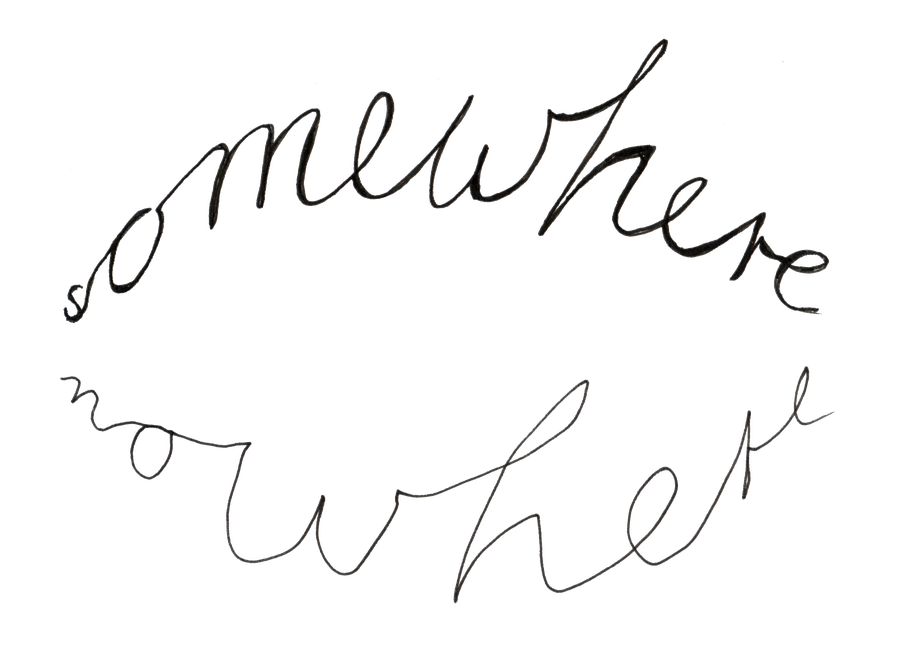

Stretched out across all four seats of the bus (do like the locals), I found a deep and recovering sleep. I only woke up when one of the old ladies went to the toilet. Then I stared at the ceiling of the bus, wondering about the design of the seat lighting – is it intent that they look like a pit bull in the dark? I was trying to take a picture but my iPhone was not good enough (see the above picture) and my big camera too far under my seat. I took an iPhone photo anyway, posted it (the internet on the bus was excellent) and hoped that my parents were already sleeping and NOT looking at Instagram. After all, they had to get up early tomorrow morning and needed their sleep. I guessed I was safe because it was already after 10 pm. Then I turned to the side and tried to fall back to sleep. For security, I put my wallet into the zip-lockable pocket of my fleece and covered myself with my jacket. It was cuddly warm, a beautiful starry sky flew past my bus window. We were already "somewhere in nowhere" between Poland and Lithuania. In my sleep, my hands found their way into the pocket of my fleece and grabbed my wallet, everything was here. Nothing forgotten, nothing mislaid. There were no problems that I couldn't handle on my own.

The next time I was woken up by the bus driver, we had arrived. An hour earlier than announced, but this was definitely where I had to get out. I grabbed my backpack, hastily slipped into my shoes and stumbled out of the warm bus into the cold night. The old ladies looked at me from the bus, with big eyes as if they could not understand why a young woman did this alone. Tucked into my fleece, my jacket and (for the first time on my journey) my self-knitted woolen tube scarf, I put my headphones on, my fleece hoody over my head and sat on a bench in the darkness.

(The story continues.)

TO KLAIPEDA, PLEASE.

Part 1 of 4

Gdansk. After three wonderful days in Gdansk with E and B, I knew I needed some alone time. I had to organise so much stuff... I needed to make my blog run more or less by itself, and have a room where I could write. I went on AirBnB, found a room and booked it, voilà! Next stop Klaipeda. Linear distance about 277 kilometres. By bus, I would drive around Kaliningrad so the actual route was 670 kilometres long. Not ideal, but for Kaliningrad, I decided, I was not ready. I realised it, respected it and found alternatives. I booked an overnight bus on the internet. Clueless as I am, just on a random website. Big mistake.

I had already spent all my Zloty and did not have time to get more money. Luckily E & B made me a plate of exquisite pasta with spinach to eat (thank you, thank you, this was the last real meal for the next 72 hours), E was so nice to hand me 5 Zloty for the bus. My bus would leave at 7 pm at the bus station on platform 11. No idea where that was. The city bus took longer than expected because of rush hour. I was getting nervous. There was so much going on in my mind. Above all, I was glad to be alone. Despite all the nervousness, I knew that if I was late, at least only I had to face the consequences that would arise. I would not have jumbled anyone's plans up by making once again the decision to take the last possible bus connection. Although it wasn't that bad... I actually had a total of 40 minutes for the 25-minute bus drive to the station. I could not have foreseen that the city bus had a 5-minute delay and that it would take so much longer than usual.

At the bus station, I followed a group of excited young people who seemed to be in a hurry and went in roughly the right direction. They went to the same bus as I did, it was wonderful. I can't really tell the Slavic languages apart. I thought they were Poles, but they were a wild mix: Ukrainians and Russians. When we got to the bus, it turned out that it went off at the right platform, but not to the right place. Its destination was not Klaipeda, but Kaunas and from there to Vilnius. The bus drivers told me that he could take me to the right country, but not to the right city. I would have to change busses in the middle of the night and wait for 1-2 hours in an unknown city at the bus station. Great. This was exactly what I wanted to avoid. The bus drivers looked at my ticket, shook their heads and cursed me in Polish. They wanted to leave and said, just get in. I was a bit helpless. Should I get onto a night bus which drops me off somewhere at 5 o'clock in the morning and doesn't even go to the destination that my ticket suggested there was a direct connection to, or not drive at all and buy a new ticket tomorrow? If there was a direct bus, I would want to get on it. I also had no way of knowing whom to trust.

The Ukrainians and Russians were gathering around to translate for me. The Polish bus driver talked to a Ukrainian who spoke Polish, who gave the information to a Russian who spoke English, who then translated for me. We managed to communicate with each other in a Babylonian hullabaloo. I had already decided. So what! I was on an adventure. The Ukrainian had developed a protective instinct for me and it did not conform with his honour to send a young woman onto a night bus without a clear destination. He advised me strongly against getting on the bus, told me that the bus driver was definitely crazy and was speechless when I went anyway. I had decided that at the end of every nowhere there is a somewhere. Besides, at the last moment, a young and very pretty woman, who understood Polish and spoke English, had joined in. I never asked her, but I think she was Latvian and just in case she could translate what the bus drivers had to tell me.

(to be continued...)