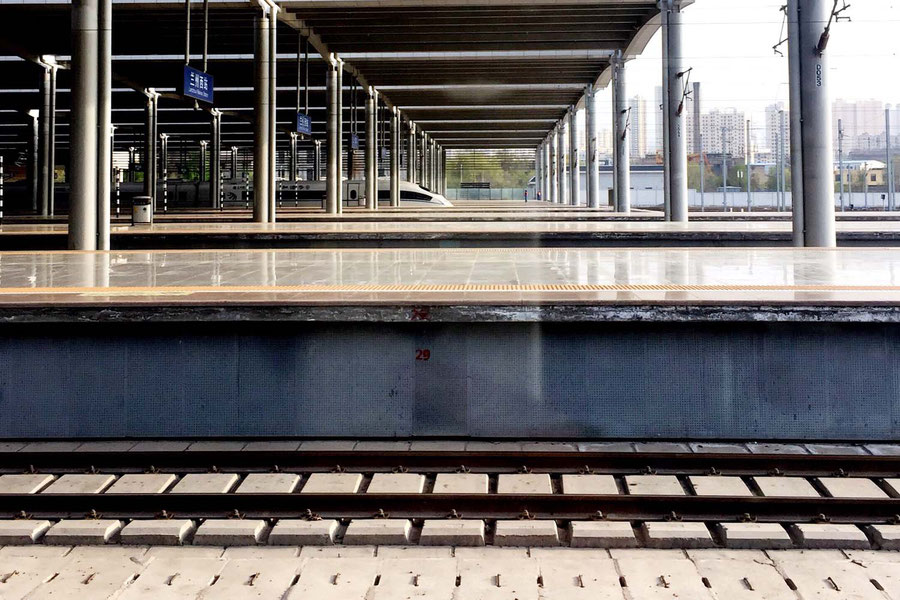

From the centre of Lhasa, I fight my way to the station. Because of miscommunication between the receptionist and I, the taxi driver demands me to pay 50 yuan for a 15 yuan journey. I stay in the back seat for a whopping 20 minutes. Finally, I give him the 30 yuan that stand on his meter. He is offended and I am annoyed. Because of my little standoff, I have thirty minutes left to catch my train. The train station square is vast. To get to the entrance I have to walk in serpentine lines across the square, through two security checkpoints and into a separate building to get my ticket. I stand in line for 20 minutes. When it's finally my turn, my phone does not load the file on my ticket number, because it was sent to save space in the cloud, so that only a pixelated black and white image can be seen. I break a sweat, I act innocent and present my ID. Fortunately that's enough. She gives me two tickets and I drag myself out to walk to the main building, where I suspect the train station. Bingo. I find train station boards and uniformed officials, who now control my passport for the fourth time and now also my tickets. Since I can not decipher the Chinese characters, I follow the crowd. Although the train station in Lhasa is a vast facility, only one train leaves.

Trains are nice. I learned in Russia and India that a travelling nation is something special. China is very similar to Russia and India in this respect. The compartment quickly fills, and the bustle of the other passengers takes over. In the morning, at noon and in the evening, ready-to-eat noodles are eaten, which are incredibly spicy. They cause my eyes to water and make me sweat. In our compartment, only one young woman eats differently. All others prefer their noodle soups. She has a rice dish that is heated by a chemical reaction unknown to me. Water is poured into a plastic container, it begins to steam, and within the next 10 minutes, the dish is boiling hot. However, this alternative doesn't seem to be widespread, yet.

Chinese people from all walks of life and earnings sit with me on the train. There is a doctor who comes from Beijing to practice her profession in Tibet. She gets 50 days of vacation a year so she can take care of her family at home. A rarity in China. Right now she is on her way to her parents. A native Tibetan is on his way to the west of his province. The language barrier is vast. In the compartment there is only one woman who speaks English (the young doctor). Everyone else looks at me with curious eyes. They would like to know more about me, but there is no way to communicate. It's too cumbersome for them to use Google translator, too incomprehensible the answers. Once again, they think I'm a millionaire because I travel. An explanation is impossible. The Chinese are far from understanding an open, curious and artistic engagement with the world. The people in the carriage with me, can't even go there in their heads.

The two nights and one day it takes to leave Tibet are uneventful. I am lying on the lowest bunk, opposite me lies a Tibetan. The upper bunks are filled with young Chinese women. Casually, the glances of the men glide under the skirts of the young women as they climb into their cots. As if they are expecting to see something. The girls don't seem to mind. Each wears tights. They know what they are getting themselves into. Otherwise, everything proceeds with friendly civility. My fellow travellers turn their attention away from me and thus leave me to contemplate the landscape, which slowly glides past us. I see an infinite number of mountains and brown deserts. Now and then we drive past what counts as an industrial area, a village or a few yaks. When it gets dark, I catch glimpses of the sky. The stars are twinkling bigger then I've ever seen. If I could venture out there on my own, nothing would get me to leave so quickly. But I'm not allowed. Consequently, I'm sitting on the train wondering if, when I wake up in the morning, we will have left the Tibetan Plateau, or not. The landscape doesn't turn green until the second full day on the train, not long before we stop at a place unknown to me. Because all the passengers get up, I follow the masses without fully understanding what's going on. Even thou no one really knows how to explain it to me, it becomes clear that they are afraid that I will refuse to go along. I am almost touched by their concern and follow demurely. The new train then continues through ever greener mountains and valleys. On my navigation app, I see that we descend. In Chengdu, we arrive at 460 meters above zero. In Lhasa, I was at 3,600 meters. Unlike during the ascension, I don't feel anything.

In Chengdu, I get on a train to Kunming. Now that I know how the cookie crumbles, I can purposefully go to my part of the carriage and crawl into the top bunk without any help. Once here, I really want to get out and see the city. As always, when I make decisions far in advance, they turn out to be mistakes. I got a two-month visa for China, and now I'm almost out of the country again, not even two weeks after entry. However, it doesn't annoy me enough to let the train ticket expire. So I venture on to the south until I disembark in Kunming.

Write a comment